Written by: Hunter Craighill

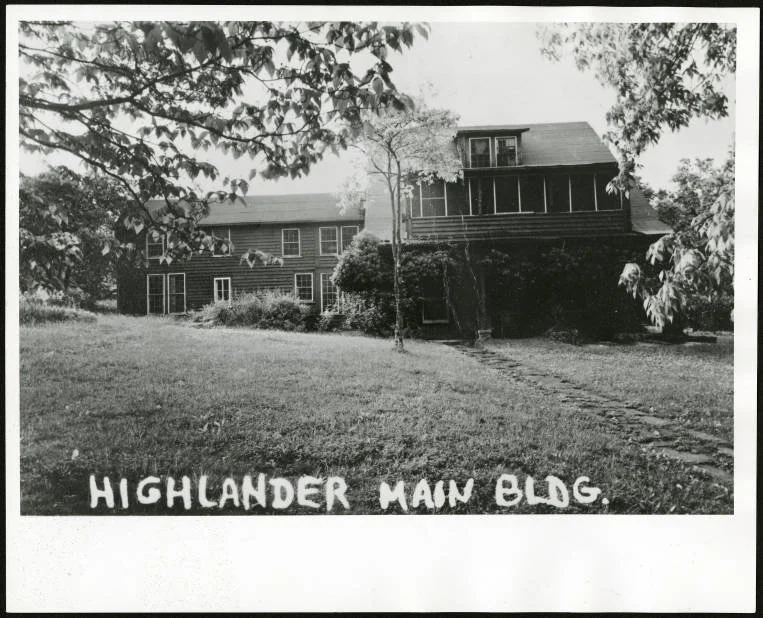

As we come to the end of Black History Month, we thought it would be prudent to remember Highlander Folk School and its role in the Civil Rights Movement and the fight against segregation. Founded in 1932 in the rural Tennessee town of Tracy City, Highlander Folk School originally began approaching the labor movements surrounding coal miners, farmers, and textile workers of rural Appalachia, but moved its focus toward the Civil Rights movement and segregation in the 1950’s.

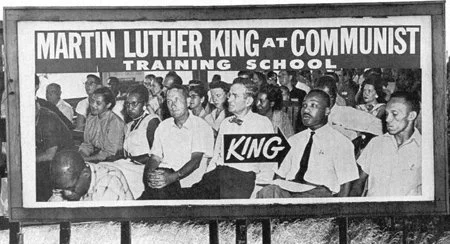

Myles Horton founded Highlander Folk School on the basis of sharing experiences to grow community knowledge, a concept he picked up in his travels to Denmark. The classes, unlike traditional educational systems, were more like workshops that focused on solving community problems. Highlander saw a lot of success with the Labor movements of the 1930s, partnering with the Congress of Industrial Organizations to train Union Organizers and leaders from across the southeast. Despite their good work, Horton and Highlander were put under fire in 1939 after a 6 part exposé accused them of spreading communist propaganda. Horton and other Highlander members, of course, denied those allegations.

In 1944, Highlander fully integrated its workshops and began shifting its focus to the issue of segregation. This shift came from the understanding that Labor Movements, in order to be successful, would ultimately have to face the issue of racism and segregation. They had their first Black speaker in 1934 but did not fully integrate until 1944 for fear of local backlash in the rural Tennessee community. They did not escape backlash and condemnation after integrating, however, as opposition leaders painted Highlander as a communist school, pushing to shut it down.

Even before Brown vs. The Board of Education reached its decision, Highlander Folk School began planning and running workshops for community leaders to prepare for integration in schools. In 1954, Septima Clark joined Highlander’s efforts to prepare for desegregation and approach the issue of voting for African Americans. At the time, many African Americans struggled to vote due to required literacy tests, so Clark alongside Essau Jenkins developed an adult literacy program at the Johns Island South Carolina community. Highlander initially funded this program, but eventually passed it over to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference which was led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Clark would later rejoin Highlander as the director of desegregation workshops.

A year later in 1955, Highlander Folk School sought to support Rosa Parks in her stand against the bus segregation laws. Parks attended workshops at Highlander and credited them with having an atmosphere of complete equality between African Americans and whites.

via peoplesworld.org

Along with their work with Rosa Parks, Septima Clark, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, Highlander Folk School also played a major role in the music surrounding the Civil Rights Movement. Following their structure of shared learning and community-engaged experience, Highlander held workshops adapting traditional folk songs into the context of the movements. One of the most commonly known examples of this came with the song “We Shall Overcome,” which became an anthem of the Civil Rights Movement. Artists and activists such as Woody Guthrie, Pete Seger, and Bob Dylan all played a part in this effort, some paying visits and attending workshops at Highlander’s campus.

As we have seen often, the work of protest and progress comes with the risk of pushback, persecution, and obstacles, all of which Highlander Folk School experienced with their efforts in the fight for desegregation. After a raid on the school’s campus in 1959 resulting in several arrests, the Tennessee Supreme Court ordered Highlander to close its doors on grounds of having communist ties.

Despite this setback, Highlander reopened the next day as the Highlander Research and Education Center in Knoxville, Tennessee, where it operated to support rural Appalachia working class people fighting for workers’ rights among other social issues.

After moving to its current location in New Market, Tennessee in 1971, Highlander shifted to assist grassroots movements against pollution and toxic dumping. To this day, Highlander continues to fight for social justice and equality for all people regardless of race, gender, and socio-economic background. Operating under the same blueprint that Myles Horton established in the 1930s, Highlander Research and Education Center will continue to be at the forefront of community organizing in support of social justice for years to come.